Table of Contents

The COVID-19 pandemic and growing movement for Black lives in the wake of George Floyd’s murder have widened public understanding of gaping health, economic, educational, and other disparities experienced by Black, American Indian / Alaska Native, Latinx, and other people of color. Public systems, policies, and practices that perpetuate inequitable outcomes undergird these disparities. In the realm of fiscal policy, this systemic racism frequently comes in the form of disinvestment generated by commercial and industrial real estate tax loopholes for the rich, which allows the politics of scarcity to reign supreme.

The politics of scarcity are not part of a child’s kindergarten to twelfth-grade curricula, but their impact shapes every aspect of their daily lives. Scarcity dictates how many blocks of crumbling sidewalks they must walk to reach a park. It dictates whether their parents can work from home during a raging global pandemic, or leave home suited-up with personal protective equipment to perform essential work–often for less than a living wage. It dictates whether children and their neighbors are more in contact with law enforcement and probation officers than supportive school counselors, tutors, and librarians. The politics of scarcity are not inevitable – rather, they are the result of specific policies that divested from our communities and have long kept us from being the Golden State for all Californians.

More than ever, our interconnectedness is our lifeline. The ability of some of us to work from home during the pandemic depends on other workers leaving their homes on a daily basis to provide essential services. The politics of scarcity weaken the threads that connect us to each other through the perpetuation of hunger, eviction, poor health care access, underfunded public schools, environmental racism, lack of worker protections, and the digital divide.

It is time to replace the politics of scarcity with a politics of equity by passing Proposition 15 to help repair California’s damaged social contract.

California and the Politics of Scarcity

California is nearly synonymous with prosperity and opportunity. Before first contact with European settlers and missionaries, it was a land of abundance for the people who toiled the earth and called it home for generations. Post-contact California has been a beacon for the ambitious, the hopeful, and profiteers alike.

California prospered in the mid-20th Century, its growth fueled by both public and private investment. During the war effort, federal spending created quality jobs and brought many new residents to the state, including African-American migrants fleeing domestic terrorism in the Jim Crow South. New Deal policies gave developers favorable financing terms that spawned suburban development and provided consumers with federally insured mortgages to purchase single-family homes. Federal “redlining” practices and restrictive covenants kept non-white households from residing in these newly developed suburbs with manicured front and back yards and other neighborhood amenities.

The residential and commercial real estate sectors were not the only ones booming. California made significant investments in public infrastructure, public education, and economic development. However, not all Californians reaped the benefits of such investment. Public and private infrastructure investments often came at the expense of communities of color. Highway construction displaced residents of color from the few neighborhoods where most of them could purchase homes. Highway construction reinforced segregation by creating physical barriers to match the social and economic barriers produced by racist policies. Local governments sited heavy manufacturing and industrial zones in the middle of these same neighborhoods.

Civil Rights, Black Power, and Farm Worker movements emboldened Californians of color to demand their full civic rights, including equal access to quality education. As demographics shifted, and social movements demanded access to the Golden State’s promise, white anti-government activists and politicians began to devise ways to limit access to California’s prosperity. The California Real Estate Association put Prop 14 on the ballot to overturn 1963 fair-housing legislation and reinstate the right to discriminate. Voters passed the measure, but the California Supreme Court later overturned it — nonetheless, conservative forces continued their efforts to limit the size of government and push for tax cuts, culminating in the Proposition 13 tax revolt.

The impact was stark. Immediately before the passage of Proposition 13, our schools had the seventh-highest per-pupil funding in the country. Since then, disinvestment and recession-era crisis budgeting have undermined our K-12 system. Despite advocates’ successes with funding measures like Proposition 30 and Proposition 55, we now rank 39th, with the largest class sizes of any state – a change that happened at the same time public schools began primarily educating Black and Latinx students.

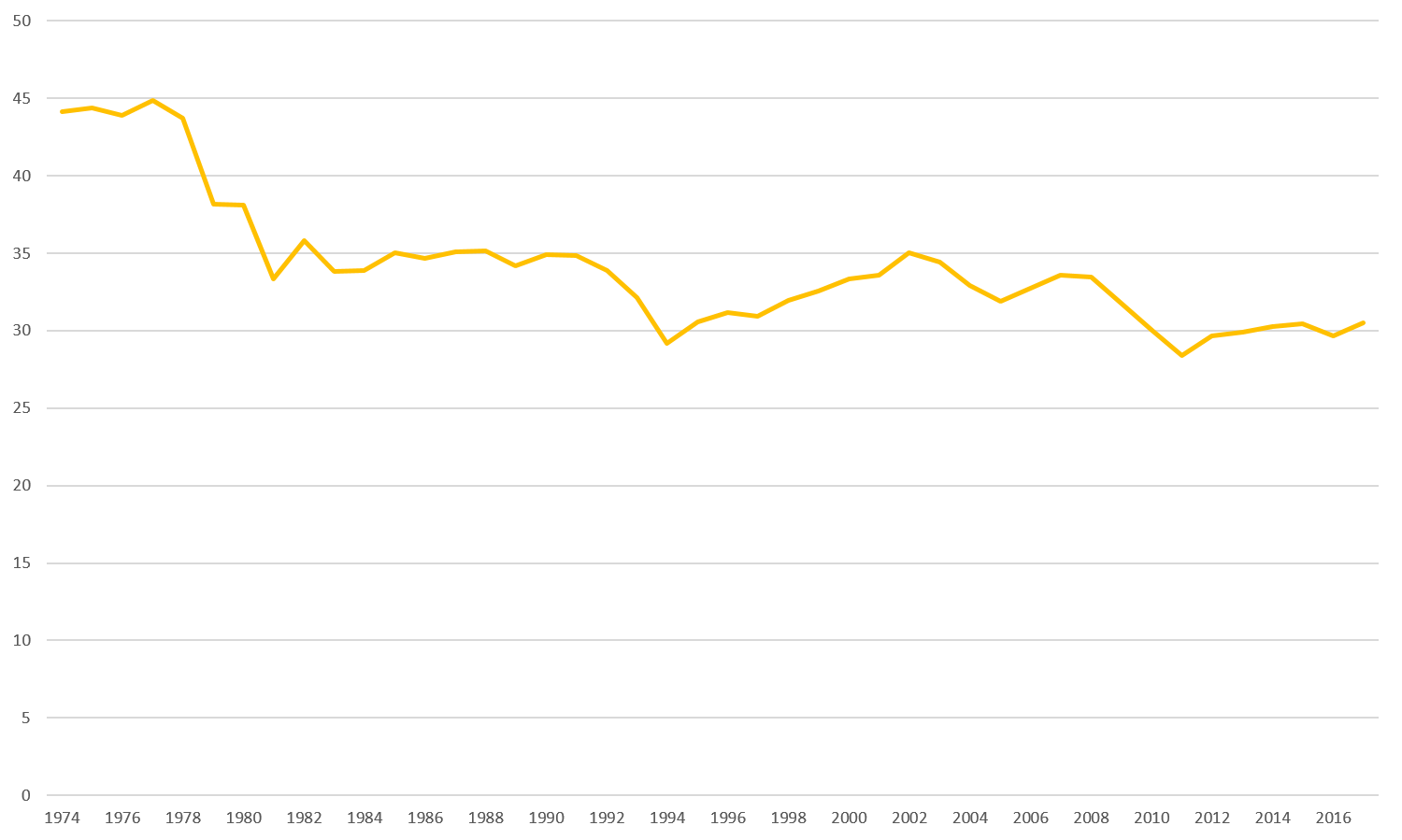

Similarly, over the past four decades California’s local governments reduced investments in parks and libraries (they dropped 4.5% and 24%, respectively, as a share of the state’s GDP). In the late 1970s, our public library system had 45 full-time employees per million California residents – a number that has dropped by a third to only 30 per million today. Our school libraries have also seen cuts: in 2011, the most recent year for which data was available, there was one teacher-librarian per 7,374 Californian students, far higher than the national average of one per 1,023.1

CA Public Libraries – FTE Staff per 100,000 population

Meanwhile, policing and incarceration were immune from the politics of scarcity as our state became a pioneer in mass incarceration – over that same period, local police and corrections spending skyrocketed 23% as a share of California’s GDP. Notably, these systems disproportionately benefit white Californians, as public safety employees are disproportionately white.2 These funding increases also occurred alongside a long-term demographic shift in the makeup of the prison population, which was 52% non-Hispanic white in 1979, but only 21% white today.3

Facing budget shortfalls, the rollback of Great Society anti-poverty programs, and increased budget demands to fight a fabricated War on Crime, local governments introduced regressive taxes and fees to fund their budgets. Since the late 1970s, the share of local government revenues coming from property taxes declined by more than 20 percentage points, and the share coming from fees, charges, and fines went up by 20 percentage points.4 The burden of these regressive policies fell on those with fewer resources.

Fees stand in the way of California’s promise of opportunity. Before 1984, California community colleges were free and helped students of color and other first-generation college students achieve economic mobility. The community college system began levying fees in 1984, and costs have steadily increased by a staggering 354% since then.5 What’s more, fees on housing construction in California are triple the national average, contributing to the housing scarcity that has made our cost of living dramatically less affordable and undermined housing stability.6

Before 1984, California community colleges were free and helped students of color and other first-generation college students achieve economic mobility. The community college system began levying fees in 1984, and costs have steadily increased by a staggering 354% since then.5

Traffic fees and fines are also especially high in California – for example, a 2017 study found that the cost of a red-light violation was $490, the highest in the nation.7 Research has also confirmed that Black and Latinx drivers are more likely to lose their licenses and be arrested due to unpaid traffic tickets than white Californians. In the city of Los Angeles, communities that have more Black residents and more lower-income residents are more likely to be targeted for aggressive parking enforcement.8

Traffic fees and fines are also especially high in California – for example, a 2017 study found that the cost of a red-light violation was $490, the highest in the nation.7

Uniting these trends, the criminal justice system has proliferated fines and fees to extract revenue from Black and Latinx communities. The California Legislative Analyst Office (LAO) calculated that by the end of 2016, debt from both fees and fines exceeded $11 Billion, and a probationer in San Luis Obispo County can expect to pay between $3,000 and $18,000 in fines over the term of their supervision.9

Divestment from services that foster prosperity for all Californians and increased spending on militarized law enforcement departments, prison systems, and other surveillance systems took place against the backdrop of a demographic shift that made the state’s white population a minority with outsized political power.

Modern-Day Profiteers

Today’s profiteers do not employ the cruel subjugation methods that decimated entire native communities and helped build the California mission system; however, their unyielding chokehold on the future of youth of color that starves school systems through the exploitation of commercial property tax loopholes is a form of cruelty and deprivation.

Harm caused by today’s profiteers cuts in multiple ways: not only do they shrug off paying their fair share of taxes, many of them harm their neighbors’ health through toxic emissions and environmental degradation. Shell Oil Company owns 400 acres of industrial land in the City of Carson, assessed at between $3.40 and $3.60 a square foot. Their last assessment was in 1975. Assessments for more recently purchased land in the area are between $25 and $50 a square foot. If the Shell Oil Company’s land were assessed at the same rate as more recently purchased land, it would generate nearly $4 million at $25 per square foot (or $8 million at $50 per square foot) in additional taxes to support local schools, parks and other services in Carson and LA County.10

Shell Oil Company isn’t the only multi-national corporation reaping the financial rewards of a flawed commercial property tax system. Together they are depriving Californians of $12 Billion in annual revenue. The rest of Californians feel the strain of paying regressive taxes, fees, and fines to fuel the budget gaps created by big corporations and their tax-loop-hole-exploiting teams of lawyers and accountants.

California And The 21st Century Politics Of Equity

Scarcity limits our imagination. It keeps our aspirations in check. It limits our dreams to increasing on-site school nurses’ presence from two to five days a week rather than envisioning the resources to fully address children’s health and well-being. We are ambitious and hopeful; nonetheless, we have learned to temper our wildest dreams because we have internalized the politics of scarcity for too long.

Thousands of communities in California have struggled to prosper despite our state’s thriving economy. If California were a sovereign nation, it would have the fifth-largest economy in the world.11 Despite the wealth created, we have the largest unsheltered homeless population in the nation. Rising housing costs in coastal cities threaten to displace renters. Economic development has created low-wage service jobs instead of career-ladder opportunities. The economy generates wealth for corporations and leaves everyday Californians with little to weather economic hardship alongside a limited, obstacle-ridden path to advancement.

A new politics of equity would replace and repair systems that have failed many Californians. Local government’s revenues would grow with the passage of Proposition 15 and enable community-driven investments. In recent years, advocates and their allies have secured both local and statewide policy wins that further racial equity. Leveraging capacity built gaining recent policy wins will shape the investment of Proposition 15 revenues.

In the United States, education is the most reliable route to economic opportunity. Community colleges that prepare students for entry to four-year universities have also been victims of the politics of scarcity. National first-year community college persistence rates for students enrolled on a part-time basis is 56.3%.12 Community college students often take years to finish what should be a two-year degree because of cost, inability to attend school and manage full-time employment. Further exacerbating the ability to complete community college is the oversubscription of core classes needed for graduation. An influx in resources to expand access to core requirement classes, build affordable student housing adjacent to community colleges, eliminate tuition fees, and provide first-generation college students with additional supports would widen the path to economic advancement.

California’s history hasn’t always been golden. Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian Pacific Islander communities have suffered staggering losses. The native people of California were displaced from their ancestral land. Spanish and Mexican settlers who had their land rights guaranteed under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo with Mexico had their claims routinely denied by the new California state government. Mexican-American US born citizens were forcibly “repatriated” during the Great Depression. During World War II, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which ordered the internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps far from the communities they had made prosperous. With little time to put their affairs in order and with profiteers lurking, they lost their land, homes, and businesses. African-Americans fleeing the South during the Great Migration were denied the benefits of Federal Mortgage insurance and saw the path to the American Dream and wealth creation narrowed by racist policies.

Proposition 15 cannot make up for all that has been lost but it can widen the path to economic advancement, safe and secure housing, educational opportunity, food security, quality jobs, and healthy neighborhoods free from toxic exposure. Every child living in the state is an equal heir to California’s prosperity. Let’s make it so by passing Proposition 15 on November 3rd.

Methodology

Catalyst California calculated inflation-adjusted State and County Area operations expenditures as a percentage of GDP from 1977-2012. Expenditure data are from the US Census Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances. Capital spending is excluded because large sums of one-time spending make year-to-year comparisons unreliable. Consumer Price Index figures used adjust for inflation are from the US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. GDP data are from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Expenditures as a percentage of GDP are shown to identify where spending represents a change in priority when compared to GDP increases.

Acknowledgements

Research and data analysis by Ryan Natividad, Tolu Bamishigbin, Chris Ringewald, and Elycia Mulholland Graves. Conceptualization support from John Kim and James Woodson (California Calls). Editing support from Leslie Poston and Matt Trujillo. Messaging and communications support from Ron Simms Jr. and Katie Smith. Design and page development by Rob Graham.

- California Department of Education, CalEdFacts – School Libraries, at https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/cr/cf/cefschoollibraries.asp. ↩︎

- See RACE COUNTS, Crime and Justice – Diversity of Police, at http://www.racecounts.org/issue/crime-and-justice/. ↩︎

- National Prisoner Statistics, 1978-2018, available at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NACJD/studies/37639. ↩︎

- UC Berkeley, Terner Center for Housing Innovation, Residential Impact Fees in California, Aug. 5, 2019, at http://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/Residential_Impact_Fees_in_California_August_2019.pdf. ↩︎

- California Community Colleges, “California Community Colleges Key Facts.” ↩︎

- Terner Center for Housing Innovation, Residential Impact Fees in California. ↩︎

- California State Auditor, Penalty Assessment Funds, at https://www.bsa.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2017-126.pdf. ↩︎

- Back on the Road California, Stopped, Fined, Arrested: Racial Bias in Policing and Traffic Courts in California, Apr. 2016, at https://lccrsf.org/wp-content/uploads/Stopped_Fined_Arrested_BOTRCA.pdf; Noli Brazil, The Unequal Spatial Distribution of City Government Fines: The Case of Parking Tickets in Los Angeles, Urban Affairs Review, June 2018. ↩︎

- California Legislative Analyst’s Office, Improving California’s Criminal Fine and Fee System, Jan. 2016. ↩︎

- Make it Fair, Policy Brief: Impacts on Los Angeles County from Commercial Property Tax Reform, December 2018. ↩︎

- “Gross Domestic Product by State, Fourth Quarter and Annual 2019” (PDF). www.bea.gov. US Department of Commerce, BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis). Retrieved 2019-07-01. ↩︎

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Persistence & Retention – 2019, July 2019. https://nscresearchcenter.org/snapshotreport35-first-year-persistence-and-retention/ ↩︎